Recently, someone on social media had a question about which was the more prevalent spelling of a word. I replied with a screenshot of the Ngram Viewer from Google Books, which is my go-to method to check such things. The response from the original inquirer was basically, “What black magic is that?”, which is when I remembered that a) it can be overwhelming to have unexpected graphs and numbers thrown in your face, and b) not everyone knows about the Ngram Viewer.

I really like having the ngrams as a research tool, so I’m going to try to explain how the ngram stuff works in a non-scary way!

First, Google Books.

When you go to google.com and search, your query sorts through the world wide web. But there are options to adjust what you’re searching. If you want to find scholarly articles, you can go to scholar.google.com, or news.google.com for news sources. And if you want to search through the vast catalog of books that Google has scanned, you point your browser to books.google.com. I expect it’s also an app on mobile, because Google Play Books is in theory a competitor to Kindle, Kobo, etc, but what we’re talking about today is the collection Google has scanned over the years from academic libraries. Unlike graphs, copyright law is something that makes my head hurt, but my understanding is that anything before 1923 is public domain and fully viewable through Google Books, while things after that have snippet or preview view available. The important part is that Google knows what the text in all those books is, and they can search through it.

Now, the Google Ngram Viewer.

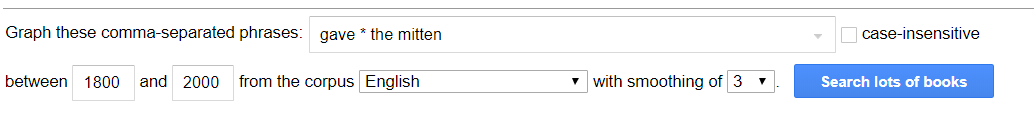

Once you have a ton of published text, its publication data, and the ability to search, you can make graphs. How often was a word used in 1887 or 1943? That’s the information that the Ngram Viewer provides in graph form.

In this ngram, I’ve asked it to query three terms: Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, and Elizabeth Gaskell. On the lefthand the y-axis shows percentages which tell how often the term was used: if I have my math(s) correct, 0.000120% indicates that for every 833,333 word pairs, one pair was “Jane Austen” in 1999. I don’t look at those numbers – unless you’re searching for extremely common words like “the” or “it”, they’re always going to be infinitesimally small. The x-axis is easier to understand: it shows time in years.

The interesting bit is the colored lines which are plotted for each term. Which way are they going and where are the bumps?

In this example, we can see that it’s not until after WWI that Austen definitively eclipses Charlotte Bronte in popularity. There’s also an interesting bump in discussion of Charlotte Bronte which peaks in 1860. Since she died in 1855, I’m going to guess it has to do with posthumous appreciation and recognition of her work, but that’s purely uninformed speculation. Elizabeth Gaskell lags below her fellow authors in popular discussion, but we can see that she follows generally the same rise and fall as the other two — there’s a noticeable dip around WWII that affects all three, for instance.

Now that we see how the ngrams work, I’ll talk about three ways that I use them as a writer.

1. Checking common spellings.

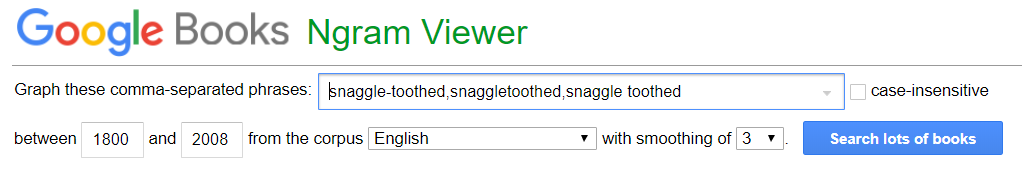

Imagine, if you will, that I’m merrily typing along on my work in progress, and I come to a description of an unsavory character. Shoot, I say to myself, is it “snaggle-toothed” or “snaggletoothed” or “snaggle toothed”? Spellcheck doesn’t like “snaggle” at all, so now what am I to do?

Pull up books.google.com/ngrams and type all three options into the query box, separated by commas, like so:

Once I hit the “Search lots of books” button, I have my answer:

“Snaggle-toothed”, the hyphenated option, is the most prevalent, though snaggletoothed as a single word has also gained popularity in recent years. What happened in WWII that involved snaggle-toothed characters? That is a question for another day, because in this theoretical example I should get back to writing and not get side-tracked!

2. Checking for anachronistic usage.

If I’m writing a historical book and I look at that graph, I see that snaggle-toothed didn’t take off until the twentieth century. If my story is set in the nineteenth century or earlier, then I won’t want to use that word in character dialogue because my characters wouldn’t know the word! I might not want to use it in my book at all.

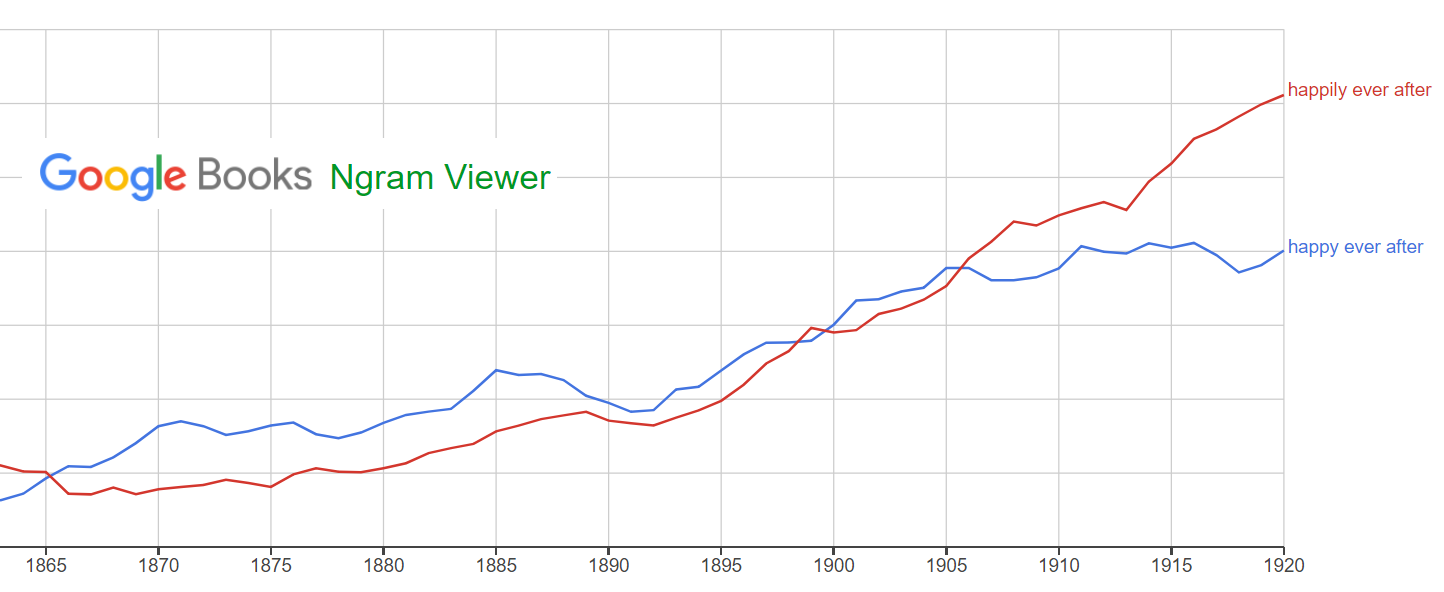

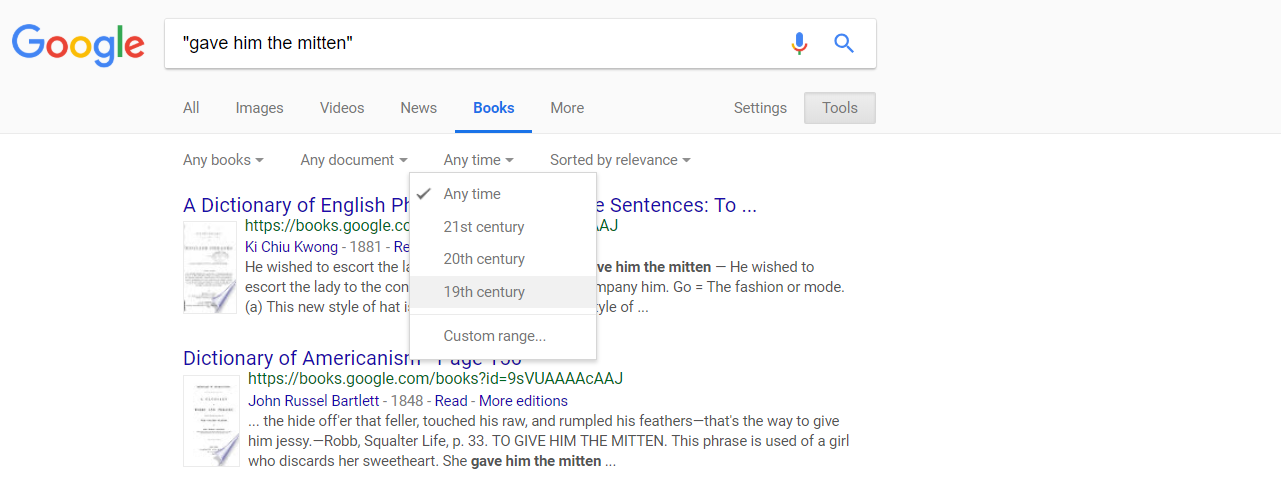

Somewhere, I ran across the phrase “gave him the mitten” as a euphemism for a woman refusing a man’s proposal. I immediately wanted to use it in my book, but wanted to double-check its validity.

This time I put in a wildcard in the query by replacing “him” with an asterisk. That means that Google will give me up to ten phrases that match “gave (something/someone) the mitten” in the graph.

In the resulting ngram, I see that “gave her the mitten” doesn’t even show up, indicating that “gave him the mitten” was a phrase used more often than one would expect if we were only dealing with people politely passing knitted items around in wintertime. It was also more prevalent in the late nineteenth century than it is today, which also suggests a phrase fallen out of fashion, because mittens themselves have remained popular.

For investigating anachronisms, I often use two other methods. First, the online etymology dictionary at etymonline.com is a great friend of mine. Second, the non-graph search on books.google.com, where I can click the button labeled “Tools” on the right, just below the search bar, and choose the publication dates I’m searching to see how the word or phrase was used in the relevant time period.

3. Checking regional word usage.

In the Ngram Viewer, I can also adjust the language of the books it is searching through. Am I writing a Regency romance? I can switch to British English and see if that makes a difference.

Here’s a British English search for color vs colour:

And here’s the same search in American English:

…which again provides different opportunities for rabbit-holing. How interesting that American-English took 50 years after the Revolution to diverge, and that both instances seem to be converging!

So that’s three ways to use the Google Books Ngram Viewer to check appropriate word usage, or go rabbit-holing down through the history of words! I’ll be back with a bonus post on Wednesday with one further use of the ngrams for research, but if this sort of thing is useful/entertaining to you, there are two similar tools (that I know of) for you can play with!

- Google Trends – The Ngram Viewer defaults to dates between 1800 and 2000, and can only be extended through 2008, but Google Trends provides similar graphs for the internet for 2004 forward.

- Everyone Has A Name – Pretty graphs from US census data to show baby names by year from 1880 through 2014. It’s a Flash based site and apparently Flash will die in 2020, so play with that one while you can!